On the surface, sleep looks like a colossal waste of time. Think about it. We spend about a third of our lives lying down with our eyes closed…basically doing nothing!

It’s easy to see why high-achieving people throughout history – like Thomas Edison and Benjamin Franklin – aspired to get by with less of it.

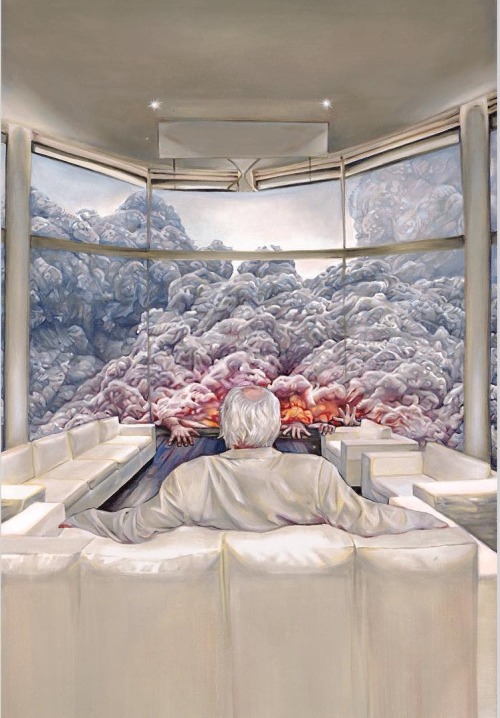

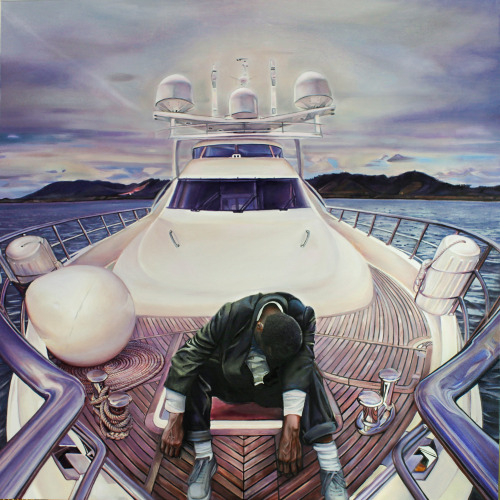

Even today, people who are trying to maximize productivity are prone to shortchanging sleep so they can get more done. Twitter founder and CEO Jack Dorsey, for instance, reported he was only getting four to six hours of sleep per night in 2011. I’m sure you can think of plenty of others who have made similar compromises. You may have even done it yourself.

For most of us, though, this is not likely to be a winning long-term strategy. For one thing, we know now that sleep loss increases our risk of chronic disease, including diabetes, atherosclerosis, obesity, and more. Inadequate sleep duration and poor sleep quality are linked to most of the great maladies that plague the modern industrialized world.

But even beyond that insidious physical toll, research is now revealing that sleep loss also has a negative impact on our cognitive abilities. We need sleep for focus and attention, for staying alert, for learning and remembering things, and for a host of executive functions that are required to be at our best at work and in other endeavors. So, you might gain an extra hour or two if you cut out some sleep, but your ability to perform mentally during that time may be compromised, and you may actually get less done in the long run. Or the quality of your work may suffer.

You might think this doesn’t apply to you. But bear in mind that the cognitive impact of partial sleep loss can be quite subtle, and difficult to recognize in ourselves. This, of course, is why we need controlled studies to elucidate these effects.

And that brings me to our guest for today.

GUEST

In this episode of humanOS Radio, Dan speaks with Jeff Gish. Jeff has a Ph.D in Management from the University of Oregon, and is presently a professor of entrepreneurship at UCF.

His research focuses on the behavior of entrepreneurs, including the processes through which entrepreneurs decide to found new ventures and make business decisions. Recently, he has begun to explore how these processes are influenced by day-to-day variations in biological dynamics – including sleep.

He and his colleagues recently performed a series of elegantly designed studies which investigated how sleep, or the lack thereof, might affect two functions that are fundamental to the role of an entrepreneur: the capacity to generate new business ideas, and the ability to assess the viability of business ideas being presented to them.

In the first study, they recruited 784 practicing entrepreneurs from all over the world, who had been asked to report on their sleep the previous evening. Each person read three new venture executive summaries, which had been reviewed and rated by a panel of experts. Two of the three were designed to be relatively promising. But one of the venture ideas was crafted so that it superficially appeared to work, but had attributes that rendered it less commercially viable when examined carefully. Entrepreneurs who slept less were more likely to favor the dubious pitch over the better ones, when compared to entrepreneurs who were well rested.

The second study goes a little bit deeper. The researchers followed over a hundred practicing entrepreneurs over the course of two weeks. Every morning, the entrepreneurs would report on their sleep the previous night. Then, in the afternoon, they were asked to appraise a new venture idea. Similar to the previous study, these ideas varied in quality, and were manipulated so that some were more challenging to interpret from a business standpoint. And much like the prior study, the subjects had a harder time evaluating business ideas that exhibited less obvious qualities when they slept less. This study is particularly useful because it is comparing the participants to their own performance over the course of the study, rather than to their counterparts (we know that some folks need more or less sleep than others).

For the last phase, Jeff and his team wanted to isolate the effects of sleep as a variable, rather than rely upon self-report. To that end, they performed a sleep restriction experiment. Business students were randomly divided into two groups – one which got at least seven hours of sleep, and one that stayed awake in a lab for 24 consecutive hours. Both groups were asked to do the same venture summary ranking task from the first study, and were also asked to come up with business ideas for a new technology. The group operating on total sleep loss was much more likely to prefer the questionable venture plans, and their own ideas had significant issues too.

These studies overall suggest that sleep plays a vital role in the cognitive processes behind successful entrepreneurship, and losing sleep makes it harder to recognize how a new technology or service might align with a market.

To learn more about the study and what he found, check out the interview below!

LISTEN HERE

On Soundcloud | Spotify | Apple Podcasts | Google Play | Stitcher | iHeartRadio | Overcast.fm | YouTube

YOUTUBE

SUPPORT

Have you considered becoming a Pro member of humanOS.me? It costs just $9.99 per month, and when you go Pro, you get access to all our courses, tools, recipes, and workouts. Pro members also support our work on blogs and podcasts, so thanks!

LEAVE A REVIEW

If you think other people would benefit from listening to this show, you can help us spread the word by leaving a review at iTunes. Positive reviews really help raise the profile of our show!

TRANSCRIPT

| Jeff Gish: | 00:00 | You don’t get enough sleep. The entrepreneurs aren’t as good at identifying opportunities, coming up with ideas and they’re not as good at evaluating opportunities that are placed before them. |

| Dan: | At the surface, sleep looks like a colossal waste of time. Think about it. We spend a third of our lives laying down with our eyes closed, basically doing nothing. It’s easy to see why high achieving people throughout history like Thomas Edison and Benjamin Franklin aspired to get by with less of it. And even today, people who are trying to maximize productivity are prone to shortchanging sleep so they can get more done. | |

| 00:11 | Twitter founder and CEO, Jack Dorsey for instance, reported he was only getting about four to six hours of sleep per night in 2011. For most of us, though, this might not be a winning strategy. For one thing, we know that sleep deprivation increases our risk for chronic disease including diabetes, atherosclerosis, obesity, and more. | |

| But even beyond the physical toll, research has revealed for focus and attention, for staying alert and for learning and remembering things. And for a host of executive functions that are required to be at our best at work, and in another endeavors in life. | ||

| Meaning that you might gain an extra hour or two if you cut out some sleep, but your ability to perform mentally during that time may be compromised and you may actually get less done in the long run. Your work may suffer. You might think that this doesn’t apply to you, but bear in mind that the impact of sleep loss can be very subtle and hard to recognize in ourselves, which is why we need controlled studies to elucidate these effects. | ||

| Why I’m pleased to have Jeff Gish on the show, and has also personal experience in venture development. He founded multiple businesses with successful exits and now invests in other founders and their ventures. His research focuses on entrepreneur behavior, including how entrepreneurs decide to found new ventures and make business decisions. Recently, he has begun to explore how day to day variations and biological dynamic influences affect these processes including sleep. | ||

| He and his colleagues recently performed a series of elegantly designed studies examining how sleep or the lack thereof, affected the ability of entrepreneurs to generate business ideas and to assess the viability of business pitches that were presented to them. The study suggests, unsurprisingly that sleep plays a vital role in the cognitive processes behind successful entrepreneurship. Jeff, welcome to the show. | ||

| Jeff Gish: | Thanks Dan. It’s a pleasure to be here. | |

| Dan: | Tell us a little more about your background and what made you interested in the role of sleep in cognitive processes that underlie entrepreneurship. | |

| Jeff Gish: | 02:10 | I had a business for seven years. When I sold it, I had 57 employees and I was one of the people who was trying to get by on less sleep and I frequently uttered phrases like, sleep’s a waste of time. Sleep is for weaklings. I’ll sleep when I die. I don’t know if I actually said those things, but I was thinking them and I had conversations around them with colleagues who are also in business. They were of the same attitude. And I always knew in the back of my mind that’s probably not a great way to operate, but there is a trade off, right? |

| As you mentioned before, you get extra time if you sleep less. So I was frequently choosing extra time to devote to my venture and oversleeping and I think a lot of my colleagues who were small business people and high-growth entrepreneurs themselves were doing the same thing. | ||

| 02:13 | And so reason I got interested in this is because I sold my business and I was deciding what’s next in life and I decided to pursue a PhD at University of Oregon. And as I was entering the world of academic research, I started talking to a person at the University of Washington. He’s a co-author on this paper and he started telling me because of my pension for drinking coffee and sleeping less, that I was basically addicted to crack and I needed to change the way I thought about it. And I thought, okay, that’s a really one sided viewpoint, but it got me thinking. | |

| And so we started talking more about the types of deficits that exist when you don’t get enough sleep. And in those conversations we started a research project, and as I went through my PhD and now I’m an assistant professor at University of Central Florida, we continue to study these things and we’ve got several papers now on sleep. And this person during that time at the University of Washington, his name is Chris Barnes has really become the sleep guy in organizational research. | ||

| 02:20 | And so this is and entrepreneurship paper, but he does research all over the map on how sleep affects people and organizations. And so I was happy to have him on his paper. He contributed intellectually to the work. And what we find in the paper at a very high level is entrepreneurs aren’t as good at identifying opportunities, coming up with ideas, and they’re not as good at evaluating opportunities that are placed before them. You don’t get enough sleep. So that’s the basis of the research. | |

| You brought up Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Edison who also uttered phrases like “Sleep as a waste of time.’ That’s a direct quote from Thomas Edison. There are people who, whether it’s because of recent research that exists or through their own intuition in business who are trying to buck that trend and go a different direction and I’ll bring up Jeff Bezos as an example who suggests that he needs at least seven, eight hours of sleep per night. | ||

| That fits right in line with the National Sleep Foundations recommendations and Arianna Huffington has gone one step further to start a sleep revolution. That’s title of her most recent book on the topic, because she was one of those people who took her experience of waking up in a pool of her own blood because she fell out and hit her head due to lack of sleep to get her to say, all right, this is crazy. This life is crazy. I need to think about human sustainability and wellbeing if I’m going to be successful in business. It’s not everyone who is successful doesn’t sleep a lot, and it’s possible that those people that don’t sleep a lot, that are successful, are successful despite the fact that they don’t sleep a lot. | ||

| Dan: | Sleep revolution is an apt idea in that we are in a new time where historically many had viewed sleep as this monumental waste of time. A time where if those who are serious about their work would be getting additional hours in the day committed to their work. But I think because of now new understanding of the importance of sleep and having those ideas permeate, we are at a place now where the pressures to get less sleep exist, and are probably as great as ever, but the awareness that it is important is also growing as well. | |

| So it’s nice to see your work directly relating to entrepreneurship because high growth companies, the demands placed upon these individuals are great. Oftentimes doing the jobs of multiple people. And so you have to then have such a clear understanding of the value of sleep that you have to counteract the pressure. | ||

| Let’s talk a little bit about cognitive processes. For a good chunk of the study, you’re testing cognitive processes or similarity comparisons and structural alignment. Something that might not be familiar territory for a lot of us. So tell us about structural alignment theory. And the differences between superficial and structural similarities and how it relates to cognitive processes that entrepreneurship demands of us. | ||

| Jeff Gish: | Sure. So thinking about structural alignments area at a very high level, you can use the analogy of an iceberg. At the tip is superficial alignments between a new technology and a market that it might be applied to. So these are two different things that you’re comparing to one another. And I use the iceberg analogy, even though it’s cliche because it’s just a nice visual way to think about it. So at the surface, a new technology and a market might look like they match. For example, child psychologist at Stanford University designed some educational tool for kids in K through 12 education. | |

| Superficially, that makes a lot of sense. Structurally, is actually why that new technology might work for a particular market. If that technology that was developed at Stanford University doesn’t apply to the problem that those K through 12 students are experiencing, it’s probably not going to have much commercial success, even though it seems superficially like those two things are aligned. | ||

| 05:00 | Let’s take the example of ADHD and attention deficit. If the Stanford psychologists are working on something that alleviates stress in students, they probably won’t help that market that’s looking for a nonmedical solution to ADHD. And so structurally that idea doesn’t work even though superficially it does. | |

| Under the surface, if they do match, they don’t have to match superficially. The tip of the iceberg does not matter in commercializing a technology for a particular market. It’s the structural stuff that does matter. The how and why a technology works for a market and even potential benefits and problems that a market might experience when using and adopting a new technology. | ||

| Let’s say in that same example where I was talking about, maybe it’s not Stanford child psychologist, it’s some totally unrelated field. It’s a technology developed for adults, but it has to do with, let’s say it’s a technology designed for pilots and paying attention while you’re flying a plane. | ||

| This is a real commercial example that I’m drawing from, and I won’t get into too many details on the example, but let’s just say it’s a tool designed to monitor pilot’s attention while they’re flying a plane. Kind of an important thing, especially if you’re flying precious cargo, including humans. | ||

| 06:01 | Developing attention tools for pilots is not the same thing as developing ADHD solutions for K through 12 education kids. Kids and the pilots are two totally different markets, right? But structurally, there’s a lot of congruity there. Monitoring attention of pilots, you’d be monitoring a kid’s attention doing some type of a task when it turns out that this simulator technology that was made to monitor pilot’s attention was also applied in a strategic partnership with the Sony platform for a racing game such that kids with ADHD could use it and find a nonmedical solution for attention deficit disorder. | |

| The way that it works as it makes a race car driving game harder to control, just like in the simulator, it made it harder to control the plane controls if somebody’s attention wavered. Structurally, a lot of the benefits that one market gets applied to another one, and so that’s why this technology worked with a new market because structurally they were aligned even though superficially they were not. | ||

| Dan: | I see. The core elements of what is making this technology or mechanism work. In one population would look very different but should still work if it’s assessing elements of cognitive processing that should apply to other populations as well, at least theoretically. | |

| Jeff Gish: | In practice too. This is a flight simulation technology was actually developed at NASA for shuttle pilots and it was applied with a strategic partnership with one of the PlayStation platforms and received venture funding. So you can argue about the efficacy of whether it makes sense for kids with ADHD to play more video games, but it did get some commercial backing and the way they monitored attention was with an EEG helmet, so it wasn’t like this was a really affordable thing, but there are a lot of parents who don’t want medical solutions like Ritalin and other drugs for their kids when they have ADHD. So there was some traction and some commercial success in that area. | |

| Dan: | Broadly speaking, how might sleep or lack thereof, affect these cognitive processes, which then underlie opportunity ideation and assessing venture ideas. Moving over to the sleep element, why do you think that this connection is meaningful? | |

| Jeff Gish: | There’s a lot of sleep research out there that talks about how we have cognitive deficits when we’re sleep deprived. We make decisions with more of an emotional tone tied to our memories. When we were trying to draw on rational decision making schema, we’re not able to because there’s emotions tied to that if we don’t sleep well. The sleep enables us to shed affective tone that surrounds our memories. | |

| If you’re thinking about a new presentation, something that’s being presented to you right now, usually you compare that to your memories, first of all, so your memories could be changed based on the fact you didn’t get sleep. But perhaps more importantly, there are FMRI studies that say we use a different portion of our brain to make those decisions when we are sleep deprived. | ||

| So if you’re using a different portion of your brain or for different portion of your brain is firing when you’re sleep deprived, then when you’re well rested, it’s unlikely that you would make a similar decision. | ||

| In this situation with entrepreneurs, we did three different studies. Two of them with entrepreneur samples and one with entrepreneur student samples. So students who are studying to be entrepreneurs. The first one was 780 entrepreneurs around the world where we compared them to each other to see if people who had slept less were able to pick out those structural alignments between a technology and a market that it would be applied to. | ||

| 08:38 | It turned out that people who were more well rested did a better job of picking out those structural alignments and didn’t rely on the superficial comparisons between the market and the technology. The common pushback that I would receive when I started talking to people about that study, I gave this presentation to a group of 250 angel investors and entrepreneurs. A few of them came up to me afterwards and one was particularly [inaudible 00:11:01] and said, “Hey, that’s not me. I don’t need to sleep as much as everybody else. I get by on three to four hours of sleep. | |

| So what can you say that provides evidence that I’m not different?” At the time, I couldn’t really say anything when I was talking about that study where I compared entrepreneurs to each other. Because there are different levels of sleep. I think those are overblown. You talked about how some people get by on very few hours of sleep and there’s a thing called short sleepers, but even the highest estimate of those are 1% of the population and there’s 12% of people, at least in the United States who claim to be self employed. And so even if everyone who is a short sleeper, self selected into an entrepreneurial career, | ||

| Dan: | 08:52 | That doesn’t happen by the way. |

| Jeff Gish: | We’d still have a problem with all entrepreneurs going out and saying that sleep isn’t so important. So I didn’t have an answer for that person at the time. But the second study helps speak to that question. What if I don’t need as much sleep as everybody else? So the second study compares entrepreneur to him or herself. | |

| 09:24 | Over a hundred entrepreneurs around the world, six different continents are represented in this sample, and I follow them for two weeks, and I check in with them twice per day. Once in the morning, once in the afternoon. And I ask them about their sleep in the morning and then I had them evaluate opportunities, particularly paying attention to whether they can tap into the structural alignments between a technology and a market that it’s intended for. | |

| Turns out that even if during the course of the study, you average five hours of sleep, you at least are sleeping less than a person who sleeps seven hours on average. You’re better at evaluation when you get six hours then that person who has an average of five. And that person can then say, okay, I only need five hours of sleep, but I’m better at evaluation of opportunities when I get six. And it tells me that maybe you don’t only need five hours of sleep, especially if you’re a practicing entrepreneur, because you’re more willing to go with those superficial judgments about an opportunity than getting deeper and looking at the structural lens. | ||

| Dan: | 09:36 | I’m glad you did the second study because showing that within person comparison over the course of couple of week period is really critical. And I call the effects of sleep over time, meaningful but invisible, where you can acclimate to the feeling of getting better sleep or less sleep and it all sort of feels normal. And so showing people objective data that indicates that they are thinking better is a really good piece of information to have to show these folks. It is very common for people to feel I do great. I don’t need sleep. |

| So how did you come up with the venture ideas that were presented to participants and how did you manipulate them to capture effects of sleep deprivation. | ||

| Jeff Gish: | Well, it’s hard to say verbally. I usually have the aid of slides, [crosstalk 00:13:21] show people how I manipulated. But we can go back to that NASA example with the monitoring pilot’s attention. I came up with two weeks worth of businesses, so 14 different opportunities, entrepreneurs evaluated and you evaluate one per day. There are two different things that I changed. I changed the superficial alignment to be aligned or not. And then I changed the structural alignment to be aligned or not. | |

| And so what that NASA example, the real example, the real world example was the technology was developed by NASA engineers for shuttle pilots. That is not aligned with K through 12 kids in education. But structurally the alignment is there. It was made to monitor a pilot’s attention and kids who are suffering from ADHD could also benefit from having their attention deficit monitored. | ||

| So structurally that’s aligned. If I change the superficial alignment, what I’m changing is instead of NASA scientists developing it, it might be separate child psychologists who are developing a new technology for a nonmedical solution for ADHD, K through 12 kids, right? So then it got superficial and if it’s made for attention vigilance, then it’s also structurally aligned. Right? So then it’s obvious you don’t have to go deeper than superficial level in that particular manipulation. | ||

| If I want to change the structural alignment, I might say, and I think I mentioned this earlier, I might adapt it so that the technology is developed to monitor stress. So if the technology’s developed to monitor stress, that is not analogous with helping attention deficit. And so structurally the how and why or the benefits and problems of that technology for that market don’t work. Right? So you can modify that. | ||

| And so you have superficial and structural alignment. I call that an obvious good opportunity, right? You don’t have to go deeper than superficial level to make judgment on that one. Same thing if you have a poor, superficial and structural alignment in that particular situation. You don’t have to go deeper than superficial level to say this isn’t a good idea. This idea will not have commercial success. But it’s in the non-obvious conditions where I’m interested in whether sleep plays a role. | ||

| 11:34 | And so in the NASA example where the superficial alignment wasn’t there and technology was developed for pilots applying to K through 12 kids, superficially, it wasn’t aligned, but it was designed for attention. That’s a non-obvious good idea because there are specific benefits and the how and why work for that particular market. And so there’s also non-obvious bad ideas where they’re superficially aligned, but structurally they’re not. | |

| So in those two situations you’d get multiple of these over the course of the study if you’re an entrepreneur, who is going through the study. And each day will be a new opportunity. You get served one of those conditions and sure enough in those ones where you didn’t have to go deeper than the superficial level, it’s superficial structural match, either high or low. Sleep didn’t matter because you didn’t have to go deeper than the tip of the iceberg. To go back to the iceberg analogy. [inaudible 00:15:46] the tip of the iceberg to make a judgment on whether this venture would have commercial success. | ||

| 11:36 | In those not obvious opportunities where the deficits exist and where errors occur, and it turns out that when you sleep less than normal for yourself, you make errors in both the non-obvious good opportunities and the non-obvious bad opportunities. So results in those matching conditions and when there’s mismatch, non obvious opportunities. When you sleep less than yourself, you’re worse at evaluating those opportunities. | |

| Dan: | Did you assess at a baseline the participants capacity to make determinations on these types of assessments and then look to see the variable of sleep and how that influenced their ability? Or did you need to because you’re doing day by day assessments and you could then just look at last night’s sleep and today’s performance? | |

| Jeff Gish: | Well, the study materials were vetted. Some of them are in the literature, some of them I wrote as analogous to the things that are already in the literature. So they’ve been verified and vetted, and there’s published peer reviewed research that talks about how this is how expert entrepreneurs make decisions, right? So we are comparing entrepreneurs to themselves on previous nights. And so I think even if you’re not good at uncovering these things, these structural alignments, let’s say you have a low baseline level for going beyond superficial level and looking at structural alignments, even if you have a low level, it gets worse when you don’t have sleep. | |

| That’s the commentary that I can rely on with this diary study of entrepreneurs. And if you are high level, again, you are statistically worse at getting to the structure of … Let’s say you’re really good at picking structural alignments. Well, you’re worse at it when you get less sleep. And so since you’re comparing entrepreneurs to themselves, it washes out the difference in ability because we’re just comparing again an entrepreneur to his or her previous self when they were well rested or short on sleep. | ||

| Dan: | 12:42 | So these studies reveal valuable information, but they’re correlational, meaning that you really can establish lack of sleep caused the subjects to perform worse at evaluating the venture ideas. So you performed a third study where you actually directly altered sleep in the lab. Describe that procedure. |

| Jeff Gish: | Great. That’s exactly what I was thinking is that these are correlational and so can we get some causal way to say the sleep is the culprit here. And so we use a randomized trial and this is with entrepreneurship students. I would have loved to do a randomized trial of entrepreneurs, but wasn’t able to get that done. The next best thing is to do that with students. And they are entrepreneurship students. | |

| These are people who are interested in applying a new technology to a market in their future, whether it be in the near future or far future. They’re interested in this topic of entrepreneurship and they’re studying entrepreneurship, so they’re studying how to evaluate opportunities. So we randomly assigned the conditions. They opted into the study by just saying they knew that they had a chance of being randomly assigned to a sleep deprivation condition. | ||

| 13:17 | But the two different conditions were either slept at least seven hours with no naps, no caffeine, or you stayed up all night with no naps, no caffeine. So at least 24 hours of complete sleep deprivation is the experimental condition. By doing random assignment, we can assume that all of the things are equal, including gender abilities in evaluating opportunities, these types of variables that might matter for the outcome variables. | |

| And what we find is that sure enough, sleep [inaudible 00:18:36] makes a major impact on the ability to pick out these structural alignments between the technology and market. And it’s a lot stronger effect size when you use total sleep deprivation, at least in this context. | ||

| Dan: | And an important comment to make there because my PhD research looked at ecologically relevant amounts of sleep loss and the effects on the brain. So many sleep deprivation studies, will do one night of no sleep at all. Important because it can help unveil in effect if it’s there, but the sleep loss experience in society is not because of one full night of sleep loss. Hans Van Dongen who was at the University of Washington state or Washington State University had done some really important work. | |

| Looking at this with David Dinges and he shows basically at least on some parameters like psychomotor vigilance test, which is a test of reaction time, nine days of partial sleep restriction to six hours per night. You basically are performing as though you’d been up for two straight days. And so we do see the loss of cognitive capacities with just missing a little bit of sleep in healthy subjects night after night. So I do think that of course this stuff is relevant, it just sort of accelerate the effects. | ||

| Jeff Gish: | Perhaps, at least in this context, I feel like I accelerated the effects by doing total sleep deprivation. But I’ll point to another study and I’m familiar with the people you’re talking about where you accumulate sleep over time such that it’s just like being sleep deprived. | |

| But there’s another study in 2017 by Merrick and other authors on this paper, Frontiers in Neurobiology, and they’re looking at risk taking propensity, which is pertinent in the entrepreneurial context. And so they have a group that sleeps at least seven hours. They’ve got a group that is sleep restricted, so sleeping five hours per night less than the recommended amount. And they have a total sleep deprivation group too. | ||

| And they compare those groups performance on risk taking propensity. And when I’m giving the presentation to people and I talked to them about it, I said, “Which one do you think performed the worst or took the biggest risks?” I guess you should say. And most people guess that it’s the sleep deprived group. It’s actually the sleep restricted group. I’ve done a lot of thinking on why that might be. | ||

| There’s other research out there that says that we’re bad at recognizing when we have these cognitive deficits that are associated with sleep loss and sleep restriction. And so when you are totally sleep deprived, it’s very clear that you’re not making decisions the way that you might be if you were well rested. It’s very salient, but I didn’t sleep last night and I need to buckle down and focus or whatever it is you do. | ||

| You still don’t have those cognitive resources, but you slow down. And there are a lot of entrepreneurs who wear lack of sleep, like a badge of honor. So I think that when they are asleep restricted, they’re walking around as though nothing is affecting them. | ||

| 16:12 | And that’s when you’re subject to falling into these traps. Like let’s say you decided to pursue a venture that has no structural alignment, but it’s superficially aligned. That’s a big mistake. And it could cost valuable resources and it could mean the end of your entrepreneurial career. | |

| But if you’re walking around as though nothing’s the matter and sleeping five hours a night, I think it’s when people sort of push through the notion that you need sleep and get as little as possible. I think that’s the most dangerous concoction of behavior because it causes people to have the cognitive deficits and also feel like I’m just fine, I’ll push through and sleep is for weekends. | ||

| Dan: | 16:28 | I think that’s a great point Jeff. If you have missed one full night of sleep, your alertness to the fact that you are sleep deprived is like you said, it’s much more salient than it would be if you just didn’t get quite enough sleep for night after night, which is very common. And if you looked in the same paper from Van Dongen, the objective reaction time impairments accumulated over days, but there was a saturating curve with subjective sleep assessment, so your sleeping has got worse for a day or two and then it leveled out and you weren’t getting any sleepier, and that led to, as they said, this condition, which could be a underestimation of your impairment and an overestimation of your abilities, which is really problematic. And I think emblematic of modern society for a lot of people that are really hard charging in work. |

| Seeing that data is really key. So this is really interesting work from all of the work that you’ve done. What do you think are some of the synthesizing points of what you’ve found so far? Like the high level ideas. | ||

| Jeff Gish: | Maybe it’s not surprising that sleep deprivation or sleep restriction causes these types of cognitive deficits. We’ve known this for a long time, right? But I think the context of entrepreneurship is a particularly interesting one because of the culture that exists with entrepreneurs. They feel like their business is so important that they should sleep less. | |

| 17:20 | And having lived that culture and having a business myself, I totally understand the hustle and the grind and those notions. So having people, resources and organization on your back to make sure that it keeps working. So you know, when I give this presentation to entrepreneurs and angel investors, I tell them that my recommendation is not just sleep more because I feel like that’s maybe going against what entrepreneurs feel is in their DNA. | |

| I want to be part of the hustle. And so I don’t want to encourage anybody to stop hustling, even though your health might benefit if you do. What I want to encourage people to do is understand that these deficits exist. And so if you’re being pressed to make a decision on a sleepy mind, my recommendation is that you ask for time to sleep on it. | ||

| 17:35 | Instead of marching around with this badge of honor that is lack of sleep and feeling like everything’s fine making this decisions with cognitive deficits, so if you do ask for time to sleep on it, I told them that your future self will thank you because you’re going to make a better decision if you do it on good sleep. | |

| Dan: | It’s funny, my dad was a successful entrepreneur himself. Sadly, he passed away at a very young age, at 59 because of cancer and he had very bad sleep apnea. I wouldn’t doubt that some connection there was reality. The point though, however, is one of the pieces of advice that he gave me always, which stuck with me and which I apply today. He wasn’t a sleep expert, but whenever he said you’re dealing with some big decisions, sleep on it, he intuitively understood that creative process that occurs during sleep either lets you arrive at a stronger, more confident decision or seeing a situation from a different perspective than you could the night before. So I valued that advice he gave me. It’s great advice and it may have been due to intuition, but the research supports it. | |

| What other countervailing measures do you recommend for somebody in this condition who’s hustling? That’s a lot of pressure on them. What do you recommend in terms of getting better sleep? The first thing you said was know the reality of the situation. What else do you tell them? | ||

| Jeff Gish: | Sleep is done in a context, right? And so there is something called the recovery paradox where people who have autonomous high pressure careers have a hard time actually disengaging from work and sleeping. They do what’s called ruminating and thinking about something for separating on ideas. I think entrepreneur is separate from this a lot, right? So again, if something’s really important to you, there’s this paradox around recovery, sleep being one of those like recovery activities where you’re not able to disengage from work and you can’t sleep. | |

| So I guess just making things as a routine as you can is helpful. Even entrepreneur’s lives rarely feel routine, at least mine didn’t in my experience, but establishing routines such that you went to bed at a consistent time fitting with your circadian rhythm, going to bed at a similar time. We do have a 24 hour clock inside of us. | ||

| 18:45 | So this study that I’ve talked about today is looking at homeostasis. This is getting your body enough sleep such that it doesn’t feel like it needs more and your brain is making decisions on a well rested night. But there’s also the circadian processes, right? So if you follow your circadian clock and establish routines that fit with that circadian clock, you’re more likely to get a high quality, sufficient quantity night of sleep. And you’re less likely to suffer from these symptoms of insomnia that often accompany people who have a hard time recovering. Entrepreneurs fall into that recovery paradox. | |

| Dan: | One thing we’ve written about previously on our blog is either keeping a journal of what you’re grateful for or having a task journal and engaging with either one of those before bed. Which one allowed for better sleep? And the main idea was that those who wrote down their tasks for the next day instead of necessarily what they are grateful for that day ended up sleeping better because it was an ability to sort of offload the ideas that you have to address tomorrow and it potentially was reducing ruminations and allowing for people to disconnect and get the sleep that they want. | |

| Jeff Gish: | Yeah, that’s great. And there’s also some research that suggests that sleep inspires insight. This is a 2004 paper. Wagner is the author’s name, and they’re trying to figure out whether people can come up with novel solutions through another serious problem. And it turns out that if you engage with the problem before a period of rest or sleep, that you’re better at coming up with a novel insight sooner. | |

| 19:32 | You can crash through the problem and it takes a long time, but you can also figure out this novel solution that gets you to the answer a lot faster. People who have slept well are more insightful in coming up with that novel way to solve the problem. It’s a good study and they control for a lot of different things that make me believe that sleep does indeed inspire insight and is one of the inspirations for the story. | |

| That 2004 paper when you talked about practicing gratitude and made me think of mindfulness practice, and there’s a recent entrepreneurship paper from somebody who is from Oregon State University. Chuck Maritz is his name. He looked at how nothing substitutes for a good night of sleep, but mindfulness practice can help ameliorate or it solves some of these cognitive deficits that exist when you’re short on sleep. | ||

| So they used an entrepreneur sample in that paper and found that when you practice mindfulness it can help calm the mind and perhaps that’s another recommendation that would help with, I don’t know this, I’m just thinking out loud. I think that mindfulness practices may lead to better sleep as well. If you’re able to sort of cognitively process these things, they don’t keep rattling around. In your mind, | ||

| Dan: | Do you plan on continuing doing research on sleep and entrepreneurship capability? | |

| Jeff Gish: | Well, I’ve got another paper with a co-author named Amanda Williamson. She works in New Zealand and it’s where we look at innovative work behavior and how sleep influences your mood, which has a downstream effect of playing on your ability to innovate or think creatively. And it’s another ESM study. So it’s comparing entrepreneurs to themselves and it was recently published in Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice and they find that particularly for high activated moods like being happy and energetic, lack of sleep brings those down, [inaudible 00:27:20] finding with then in turn, [inaudible 00:27:22] root behavior when less sleep brings down your high activated positive effect, positive moods and brings down your ability to innovate and be creative. | |

| And so that’s another example of a paper that’s already published, but there are more in the works. I’ve got one that is under review right now and it looks at how sleep influences ADHD like tendency. So this has to do with the business example I was giving earlier, but there is a literature that looks at how ADHD plays a role in entrepreneurship. And so people who have greater ADHD tendencies tend to lean toward chasing shiny new things. And one of those things is self compliant. | ||

| And so what we find in this paper is that for both practicing entrepreneurs and for the general public lack of sleep leads to more ADHD like tendencies and increases your intentions to become an entrepreneur. And for practicing entrepreneurs, the same is true. Looking for a different and new business opportunity is increased when you’re short on sleep. And we find that that path goes through ADHD like tendencies. | ||

| Dan: | Fascinating. | |

| Jeff Gish: | 21:19 | I do other things too, but these are my sleep papers and I’m not a sleep guy like Chris Barnes at University of Washington, but it certainly is a fascinating topic for me as a former entrepreneur to study, especially somebody who has changed his mind about sleep and somebody who doesn’t sleep well. It sounds like you might have struggled with sleep in your life and I’m there with you. |

| It kind of inspired me to study these things and think about how our minds are differently and our bodies react differently when we’re short on sleep and so a few different projects and of course I do other entrepreneurship research which would be a topic for another day. | ||

| Dan: | Having been in the sciences of sleep for a long time now, seeing the direct application to work life studies into a population that can benefit from it, which is people working and doing modern work with all sorts of modern pressures. The more closely related the work is to essentially assessing entrepreneurs, you probably get greater adoption of the ideas. It’s more tangible for those who are exposed to it. | |

| Jeff Gish: | 22:08 | I think the future of the research in this area is to look at, at least in my shoes, and for the people that I work with, we’re interested in looking at the recovery paragraph that I mentioned earlier and how people might say, okay, great. When we’re short on sleep, we’re not good at making decisions. Thanks. You’re not telling me anything I didn’t know. We can start looking at how to approach effectively this recovery paradox that people who have a lot of self managed time and a lot of autonomy in their careers, they have trouble disengaging from the work. |

| So how can we get it so that people have a better ability to disengage from their work? Whether it be through journaling, mindfulness or something we haven’t thought of yet. I think that’s where the future of this research should go. I endeavor to delve into that at least in the entrepreneurial realm myself. | ||

| Dan: | It’s hard to always counteract the modern environment and those pressures. Awareness is one idea that can be helpful, but the reality is that people need to also know how to do better when they’re not engaging in what we consider ideal behaviors around this particular subject, like sleep. So knowing how to do better in the face of imperfection is a great objective. | |

| Jeff Gish: | What are the interventions? What are the levers? And that’s what I want to discover. | |

| Dan: | I love it. Jeff, thank you so much for coming onto the show and sharing your work with us. It’s fascinating. | |

| Jeff Gish: | 23:14 | Thanks Dan. Appreciate you having me. |

The post How Sleep Loss Impairs Entrepreneurship. Podcast with Jeff Gish appeared first on humanOS.me.